|

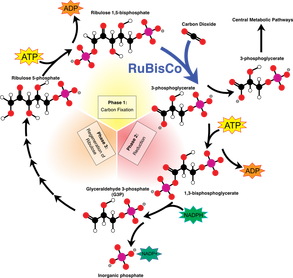

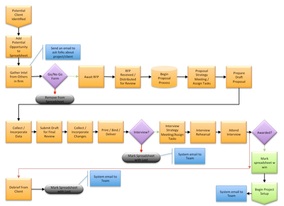

Why is a kingfisher like a bullet train? Well, it’s not. Not in the slightest. Mind you, there is a bit of an overlap in the kingfisher-bullet train Venn diagram, one that perhaps wouldn’t immediately spring to mind. You see, because of their immense speed early bullet trains caused a bit of kerfuffle. When they entered a tunnel they caused a massive air pressure buildup that manifested itself in a sonic boom at the far end. The neighbours were most unhappy, and in some cases hearing impaired. The solution came from an unlikely source – a small bird. Someone noticed that a type of kingfisher can dive into the water at high speed and make nary a splash. It had the ability to move from one medium (air) into another, more-dense medium (water) with extreme efficiency. Engineers soon launched the first bullet train to be completely covered in blue feathers. After blaming an unclear memo for the misunderstanding they quickly developed a second prototype; this model sported an exaggerated and very kingfisher-like nose. The sonic boom problem was solved, though the number of incidents of people being hit by trains skyrocketed as no-one could hear the sodding things coming until it was too late. My point is that many of our most challenging engineering problems have already been solved by a small blue bird. Wait, you know what I mean. The concept is called biomimicry. If you want to design something really clever it pays to look to nature. (Fortunately for us, Mother Nature hasn't yet worked out how to lodge a patent application.) Biomimicry has dealt predominantly with physical design challenges. It has found great application in helping us to develop machines, or things that we can otherwise hold or see. We observe the animal or plant (or bacteria) solve a problem, we build a machine that solves our own problem in a similar way. Brilliant. But biology being what it is, we’ve not yet begun to scratch the surface of the magical insights that the natural world has to offer. In particular, I’m thinking of the behind-the-scenes elements of biology – the complex chemical pathway within our cells that produces adrenaline when we need it; the triggers that lead to events like coral spawning; the forces that cause swallows to migrate across the globe. In a sense these are all processes. Something happens, which sparks an action, which kicks off a cascade of complex events, that ultimately leads to an outcome, whether that’s a fight-or-flight boost to help you out of a sticky situation or a nest of swallows in your carport. Remember photosynthesis? At its simplest, photosynthesis is the process where plants use light from the sun to convert carbon dioxide and water into food. Raw materials go in (carbon dioxide and water) and with the application of a little energy (sunlight) the plant makes carbohydrates, giving off oxygen in the process (which we find quite useful, thank you very much). Businesses are based on processes too. Raw materials go in, you expend energy (brain power, muscle, resources) converting them to something else, which ideally is more valuable than the materials you started with. It’s not just factories that work like this. Even your middle-of-the-road government department follows processes that convert one thing into another: staff receive instructions or information, then apply their skills to arrive at a solution, usually consuming resources and expending energy along the way. (Although just how much energy is open to debate. Just my little joke.) Like just about anything biological, photosynthesis is complicated. Carbon dioxide + water = sugar + oxygen is just a simplified overview. Here’s how a biologist would represent one small part of the process. Part of the photosynthesis pathway known as the Calvin Cycle. Depending on your line of work, your internal business processes might be just as complex. Diagram: Mike Jones, sourced from Wikipedia. The progression from one step to the next is governed by a host of chemical messengers and enzymes which kick in just at the right time. In business we see a similar phenomenon: you receive a message that your part of the process is required and away you go. When you’re finished you send your own message to the next person in the chain. This is what we know in business lingo as workflow. Doesn’t look any less complex than photosynthesis, huh? In a biological pathway, if something goes wrong and a message doesn’t get through the process slows down or stalls completely; arsenic is a poison because it disrupts one of the steps in cellular respiration. The reasons for a fault might be genetic or environmental but the end result is the same: a decrease in efficiency. The plant might still survive but it will struggle compared with its neighbours.

It’s the same in business. If something goes wrong and a message doesn’t get through the process slows down or stalls completely. The reasons for a fault might be cultural or individual but the end result is the same: a decrease in efficiency. The business might still survive but it will struggle compared with its neighbours. Most organisms are here today because their internal processes are as good as they can be for the environment in which they operate. They are efficient; most inefficiencies were weeded out by natural selection long ago. The plant that makes the best use of the energy it receives from the sun, exploiting it to turn raw materials into something useful, will do very well. Good messaging is crucial for successfully operating a business. If your emails aren’t clear, if your forms are hard to fill out, or if your meetings run too long and no-one listens, your signals won’t get through. And you’ll find yourself way beneath the canopy in the dark. Or eaten by a kingfisher. Comments are closed.

|

Serious stories about communication

told in a silly voice. Categories

All

Bruce Ransley

I dig a little deeper than most comms folk. From science at university, to a cold-and-wet career as a commercial diver, to working underground, and for the past 17 years as a communicator-at-large, I've had my fair share of weird experiences in all sorts of situations. It's given me a fair-to-middling grounding in all things explanatory. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed